RingoJS Modules and how to fix the Global Object

I’ve been wanting to write about modules in RingoJS for some time. The last time I did, Ringo was still called Helma NG and CommonJS didn’t exist yet, so a lot of things have changed since then.

Ringo modules follow the CommonJS Module specification, so understanding them will not only help you grasp the basic building blocks of Ringo itself, but of virtually any CommonJS implementation out there.

But Ringo modules go a bit beyond CommonJS. For instance, there are alternative ways of exporting and importing module functionality in Ringo that are more convenient in certain situations.

More importantly, Ringo’s way of implementing modules also fixes what in my opinion is JavaScript’s biggest single problem: the shared global object. And it does so without any changes to JavaScript as a language, so there’s no reason this method couldn’t be adopted by other JavaScript embeddings - even the browser, if the ECMAScript folks decided this was a good idea.

Let’s start with the basics first, which is CommonJS Modules. If you already know everything about this, you may want to skip the next section and move right to the Ringo specific parts.

CommonJS Modules

At its core, CommonJS modules are JavaScript scripts that rely on a few extra

functions and objects provided as free variables (meaning they’re made

available by the module environment) to connect to each other. These free

variables are:

-

The

requirefunction. This function takes a module identfier such as “ringo/args” as arguments and returns the exported API of the corresponding module.How exactly a module identifier (or id) is mapped to a module is described below, but essentially the id is converted to a file name such as “ringo/args.js” which is then looked up in some directory.

-

The

exportsobject. This is a plain JavaScript object used to export the module’s API. The exports object is what therequirefunction returns when the module is imported by other modules, so any property assigned to it is publicly available. -

The

moduleobject. This is a JavaScript object that provides meta information to the module itself, such as the id and location of the module itself as well as the id of the main module.

Resolving Module Ids

For the process of mapping a module id to an actual JavaScript resource, Ringo uses a module search path. This is essentially an ordered list of directories that will be checked when looking for a given module.

When Ringo is started, the module search path just contains the standard module

library and the installed packages, but it is exposed as an array-like object at

require.paths. Programs can use this to inspect and manipulate the module

search path at runtime using square bracket indexing and all the JavaScript

array methods:

require.paths[0] = "/usr/lib/ringo";

require.paths.unshift("/home/hannes/modules");CommonJS also defines a way to load modules relative to the current module by starting the identifier with “.” or “..”. For instance, requiring module “./baz” from module “foo/bar” will resolve to module “foo/baz”.

Additionally, Ringo, like a few other CommonJS implementations, allows to use absolute paths as module identifiers to load modules from outside the module search path, and using relative module ids within modules loaded via absolute id will work as expected.

Ringo Module Extensions

The CommonJS modules specification was kept deliberately small. Ringo provides some extra niceties for exporting and importing stuff. The downside to using these is that your code is tied to Ringo, but it’s relatively easy to convert the code to “pure” CommonJS, and I’ve also written a command line tool for that purpose.

One Ringo extension is the include function. This is similar to require, but

instead of returning the other module’s exports object as a whole it directly

copies each of its properties to the calling module’s scope, making them

usable like they were locally defined.

include is great for shell work and quick scripts where typing economy is

paramount, and that’s what it’s meant for. It’s usually not a great idea to use

it for large, long lived programs as it conceals the origin of top-level

functions used in the program.

For this purpose, it’s more advisable to use require in combination with

JavaScript 1.8 destructuring assignment to explicitly include selected

properties from another module in the local scope:

var {foo, bar} = require("some/module");The above statements imports the “foo” and “bar” properties of the API exported by “some/module” directly in the calling scope.

On the exporting side, Ringo provides an export function that takes a variable

number of local variable names to be exported from the current module.

Internally, this just copies the given variables to the module’s exports object,

so it’s just a way to keep a module’s exports in one place.

export("foo", "bar", "baz");Module Scope

Scope can be one of the more confusing aspects in JavaScript. (A quick Google search suggests that the main area of confusion is actually the this-object in the presence of multiple nested functions. The best way to think about the this-object is as just another function parameter with special passing and naming convention. But I’m digressing.)

Scope defines how variable names are looked up. In JavaScript there is a top-level scope - the global object - and each function gets its own scope, sometimes called the activation object. These scopes are arranged in a chain with the nested function’s scope using its surrounding scope as parent, and name lookups moving up the scope chain from child to parent.

Thus, JavaScript is largely lexically scoped, meaning that functions can access variables defined in their surroundings. This is good, because it gives us closures, one of the things that make JavaScript great.

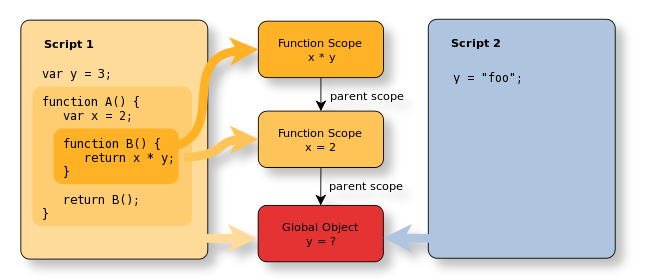

Lexical scope in JavaScript is not without flaws, however. Maybe the biggest problem is in fact the global object, which is the top level scope shared by all scripts. If multiple scripts execute in the same context, they all run in the same top level scope. If they define top level variables with the same name, the last script wins. This is illustrated in the following diagram:

To work around this problem, various workarounds have been adopted, from using only a single global variable using a special name such as “$” or “_” to shunning the global scope all together by putting all code within closures.

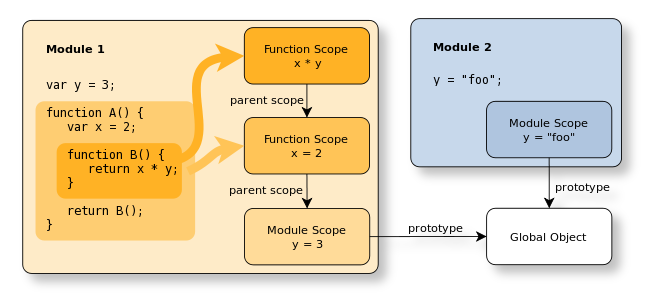

Ringo solves this problem on a fundamental level by giving each module its own top level scope to run in. The global object is still there, but it’s not in the scope chain. Instead, it is the prototype of all the module scopes, as illustrated in the following diagram:

As can be seen, the global object is no longer the place where variables are

allocated. Regardless of with or without var, top level variables will be

created in the module’s own scope. The global object with all the standard

objects such as Object, Array, or String is still there, though, providing

an environment that is totally compatible with the one found in browsers.

There you are, no more fighting for the global namespace. Now get out there and write some cool Ringo modules!

Outlook: ECMAScript Module Discussion

There is an ongoing discussion in the ECMAScript working group about getting module language features into the next version of ECMAScript, code-named Harmony. AFAIK no formal agreement has yet been reached, but the Simple Modules proposal (examples) seems to have garnered a fair amount of consensus.